The Iranian Shah: Was His Reign Truly Good For Iran?

The question of whether the Iranian Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was "good" for Iran is complex, evoking strong, often conflicting, opinions that persist decades after his overthrow. His rule marked a pivotal era in a nation with a deep, ancient history, one that has continuously shaped the global geopolitical landscape. His legacy is not merely a historical footnote but a living debate, with some remembering a period of progress and stability, while others recall an era of repression and inequality that ultimately led to a transformative revolution.

From being the heart of the Persian Empire of antiquity, Iran has long played an important role in the region as an influential power, a legacy that the Shah sought to modernize and consolidate. Understanding his reign, and whether the Iranian Shah was good, requires delving into the intricate tapestry of his policies, their intended outcomes, and their often unforeseen consequences on a society that is home to one of the world's oldest continuous major civilisations, with historical and urban settlements dating back to 4000 BC. This article aims to provide a balanced perspective, examining the various facets of his rule to help readers form their own informed conclusions.

Table of Contents

- The Last Shah: A Biographical Sketch

- Iran Before the Shah: A Land of Ancient Heritage

- The Shah's Vision: Modernization and Westernization

- The Darker Side of Power: Autocracy and Repression

- Geopolitical Chessboard: The Shah's Foreign Policy

- The Seeds of Revolution: Mounting Discontent

- The Islamic Revolution and Its Aftermath

- Was the Iranian Shah Good? A Concluding Perspective

The Last Shah: A Biographical Sketch

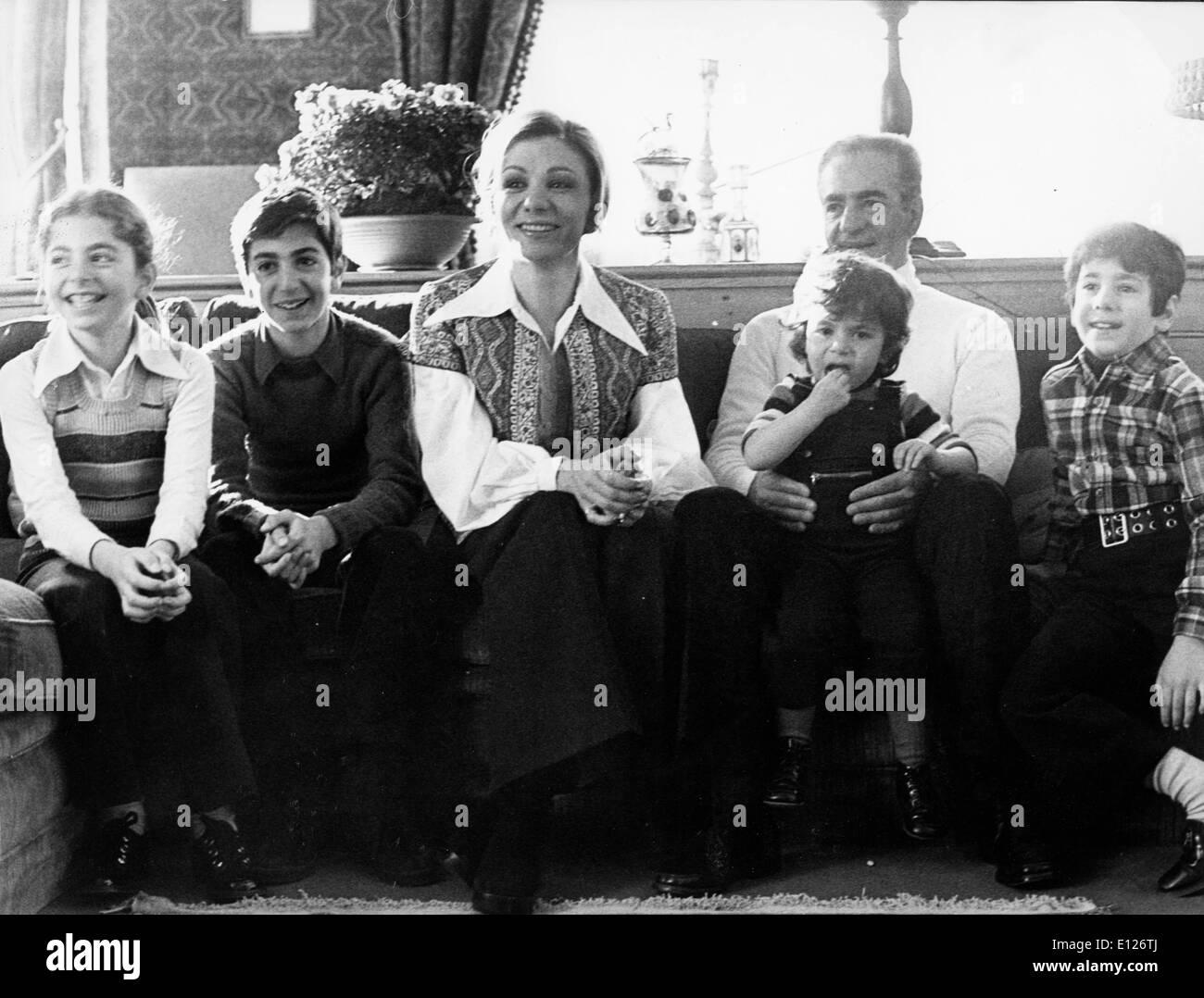

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi ascended to the Peacock Throne in 1941, inheriting a nation in flux. Born in 1919, he was the son of Reza Shah Pahlavi, a military officer who had seized power in 1925, ending the Qajar dynasty and establishing the Pahlavi dynasty. Reza Shah had initiated a program of rapid modernization and secularization, often through authoritarian means, setting a precedent that would profoundly influence his son's reign. Mohammad Reza’s early years were marked by a European education, exposing him to Western ideals and governance models that he would later attempt to implement in Iran. His early rule was challenged by the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran during World War II, which forced his father's abdication. Mohammad Reza initially held less power than his father, navigating a complex political landscape dominated by foreign influence and a nascent constitutional movement. However, his power solidified significantly after the 1953 coup d'état, orchestrated by the United States and Britain, which overthrew the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh. This event was a turning point, granting the Shah near-absolute authority and setting the stage for his ambitious, yet controversial, modernization programs. The question of whether the Iranian Shah was good often hinges on how one views this consolidation of power and its subsequent application.Personal Data and Biodata of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

| Full Name | Mohammad Reza Pahlavi |

| Title | Shahanshah (King of Kings), Aryamehr (Light of the Aryans) |

| Reign | 16 September 1941 – 11 February 1979 |

| Born | 26 October 1919, Tehran, Qajar Persia |

| Died | 27 July 1980, Cairo, Egypt |

| Spouse(s) | Fawzia Fuad of Egypt (m. 1939; div. 1948) Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiary (m. 1951; div. 1958) Farah Diba (m. 1959) |

| Children | Shahnaz Pahlavi, Reza Pahlavi, Farahnaz Pahlavi, Ali Reza Pahlavi, Leila Pahlavi |

| Dynasty | Pahlavi dynasty |

| Religion | Shia Islam |

| Key Events | Anglo-Soviet invasion (1941), 1953 Coup, White Revolution (1963), Iranian Revolution (1979) |

Iran Before the Shah: A Land of Ancient Heritage

To truly grasp the context of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's reign, one must appreciate the deep historical roots of Iran itself. Iran is home to one of the world's oldest continuous major civilisations, with historical and urban settlements dating back to 4000 BC. The western part of the Iranian plateau participated in the early developments of human civilization, showcasing a rich tapestry of cultures and innovations that predate many other global powers. This ancient heritage means that Iranian society is deeply imbued with a sense of its own history, traditions, and unique identity. Iran is a mountainous, arid, and ethnically diverse country of southwestern Asia. Its geography has historically shaped its interactions with the outside world, creating both barriers and conduits for trade and cultural exchange. The heart of the Persian Empire of antiquity, Iran has long played an important role in the region as an influential cultural, political, and economic power. Its strategic location at the crossroads of East and West has made it a coveted territory for empires and a vital link in global trade routes. The Iranian peoples, or Iranic peoples, are the collective ethnolinguistic groups who are identified chiefly by their native usage of any of the Iranian languages, which are a branch of the Indo-Iranian languages. This linguistic and ethnic diversity contributes to the rich cultural mosaic of the nation, but also presents challenges in terms of national cohesion and governance. The Shah's attempts at modernization and nation-building often grappled with these inherent complexities, trying to forge a unified, modern state while navigating deep-seated traditional and regional identities. This historical backdrop is crucial when considering whether the Iranian Shah was good; his actions were always against a canvas of thousands of years of civilization.The Shah's Vision: Modernization and Westernization

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi envisioned a modern, industrialized, and prosperous Iran, a regional powerhouse aligned with the West. His primary vehicle for achieving this transformation was the "White Revolution," a series of far-reaching reforms launched in 1963. The Shah believed that by rapidly modernizing Iran, he could elevate its status on the global stage and improve the lives of its citizens. This ambition to transform Iran was a defining characteristic of his rule, and a key factor in debates over whether the Iranian Shah was good.Economic Reforms and the White Revolution

The White Revolution encompassed a wide array of economic and social reforms aimed at redistributing wealth and power, ostensibly to benefit the masses. Key components included:- Land Reform: This was arguably the most significant aspect, aiming to break up large landholdings and redistribute land to tenant farmers. While intended to empower the peasantry, its implementation was often flawed, leading to the creation of many small, uneconomical plots and a mass migration of displaced farmers to urban centers, contributing to rapid urbanization and social dislocation.

- Literacy Corps: To combat illiteracy, particularly in rural areas, young conscripts were sent to villages to teach. This initiative significantly boosted literacy rates, especially among women, and expanded access to education.

- Industrialization: The Shah heavily invested in industrial development, using Iran's vast oil revenues to build factories, infrastructure, and a modern military. This led to significant economic growth, particularly in the 1960s and early 1970s, transforming Iran into a major oil producer and a consumer of Western goods and technology.

- Nationalization of Forests and Pasturelands: Aimed at conserving natural resources and preventing their exploitation.

- Profit-Sharing for Workers: Mandated that industrial workers receive a share of their company's profits, intended to improve living standards and reduce labor unrest.

- Creation of the Health Corps and Reconstruction and Development Corps: Focused on improving public health and rural infrastructure.

Social and Cultural Transformations

Alongside economic changes, the Shah pushed for profound social and cultural shifts, largely inspired by Western models. His government promoted:- Women's Rights: Significant advancements were made, including granting women the right to vote, run for office, and pursue higher education. Laws were passed to raise the marriage age for girls and grant women more rights in divorce and child custody, challenging deeply entrenched traditional norms.

- Secularism: The Shah actively sought to reduce the influence of the clergy in public life, promoting a secular state and Western dress codes. This included discouraging the veil and promoting mixed-gender education. Literary Persian, the language’s more refined variant, was understood to be a key element of national identity, and efforts were made to promote education in Persian, furthering a sense of national unity over religious divisions.

- Expansion of Education: Universities and schools flourished, producing a new generation of educated professionals and intellectuals.

The Darker Side of Power: Autocracy and Repression

While the Shah's modernization efforts brought about significant material progress, they were often accompanied by an increasingly authoritarian style of governance. The question of whether the Iranian Shah was good cannot be fully answered without addressing the widespread human rights abuses and political repression that characterized his later rule. After the 1953 coup, the Shah consolidated his power, gradually dismantling democratic institutions and centralizing authority in his own hands. Political parties were suppressed, and dissent was met with severe punishment. The primary instrument of this repression was SAVAK, the Shah's secret police, established with the help of the CIA and Mossad. SAVAK became notorious for its brutality, employing torture, arbitrary arrests, and extrajudicial killings to silence opposition. Thousands of political prisoners were incarcerated, and many dissidents were forced into exile. This climate of fear meant that genuine political participation was virtually non-existent. While the Shah maintained a facade of parliamentary democracy, the Majlis (parliament) was largely a rubber stamp for his policies. Critics, ranging from secular intellectuals to religious leaders, found themselves with no legal avenues for expressing their grievances, leading to a build-up of resentment beneath the surface of apparent stability. Furthermore, despite the economic growth, corruption became rampant within the Shah's inner circle and among the elite. The vast oil wealth, instead of being equitably distributed, often enriched a select few, exacerbating the economic disparities created by the White Revolution. This perceived corruption and the lavish lifestyle of the royal family, contrasted with the struggles of the common people, fueled public anger and eroded the Shah's legitimacy. The combination of political repression and economic inequality created a volatile environment, ripe for upheaval.Geopolitical Chessboard: The Shah's Foreign Policy

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's foreign policy was largely driven by his ambition to establish Iran as a dominant regional power and a reliable ally of the West, particularly the United States, during the Cold War. This strategic alignment was a core component of his vision, and its implications are central to understanding whether the Iranian Shah was good from an international perspective. Iran, under the Shah, became a crucial pillar of American foreign policy in the Middle East, a "twin pillar" alongside Saudi Arabia. The US supplied Iran with advanced weaponry and military training, transforming the Iranian armed forces into one of the most formidable in the region. This alliance served mutual interests: for the US, it provided a bulwark against Soviet expansion and a stable source of oil; for the Shah, it offered security guarantees, access to modern technology, and enhanced international prestige. The Shah also played a significant role in global oil politics. As a major oil producer, Iran was a key member of OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries). The Shah actively pushed for higher oil prices, particularly during the 1973 oil crisis, which significantly boosted Iran's revenues. While this brought immense wealth to the country, it also contributed to global economic instability and, ironically, fueled inflation within Iran itself, adding to domestic discontent. His regional ambitions were clear. Iran intervened in Oman to suppress a communist insurgency and maintained a strong military presence in the Persian Gulf. The Shah saw himself as the guardian of regional stability, projecting Iranian power and influence. However, this assertive foreign policy, coupled with his close ties to the US and Israel, alienated some Arab states and contributed to a perception among some Iranians that he was too subservient to Western interests. The current geopolitical landscape, where the US has entered Israel's war on Iran after attacking three nuclear sites, stands in stark contrast to the Shah's era of close alignment, highlighting the dramatic shift in Iran's international posture post-revolution.The Seeds of Revolution: Mounting Discontent

Despite the outward appearance of progress and stability, the Shah's reign was increasingly plagued by deep-seated discontent that eventually culminated in the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The question of whether the Iranian Shah was good often overlooks the growing grievances that festered beneath the surface of his authoritarian rule. One of the primary sources of friction was the clash between the Shah's rapid, top-down modernization and traditional Iranian values, particularly those upheld by the powerful Shi'a clergy. The Shah's secularizing reforms, including the promotion of Western dress, women's rights, and the suppression of religious institutions, were perceived by many as an attack on Islamic identity and cultural heritage. The clergy, led by figures like Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, skillfully articulated these grievances, framing the Shah as a puppet of the West and a betrayer of Islamic principles. Economic grievances also played a crucial role. While oil revenues soared, the benefits were not evenly distributed. Rapid urbanization led to overcrowded cities and inadequate infrastructure. Inflation soared, making basic necessities unaffordable for many, particularly the urban poor and the traditional bazaar merchants. The land reforms of the White Revolution, while intended to help farmers, often led to their displacement and migration to cities, where they faced unemployment and poverty. This created a large, disenfranchised urban underclass that was highly susceptible to revolutionary appeals. The lack of political freedom further exacerbated the situation. With all avenues for peaceful dissent closed off by SAVAK's repression, opposition movements were forced underground or into exile. Intellectuals, students, and religious figures who dared to criticize the Shah were imprisoned, tortured, or silenced. This suppression of dissent meant that popular anger and frustration had no legitimate outlet, building up pressure until it inevitably exploded. The Shah's inability or unwillingness to engage with genuine public grievances, coupled with his perceived arrogance and detachment from the common people, ultimately sealed his fate. The widespread feeling that the Shah's rule was fundamentally unjust and unresponsive to the needs of the majority was a powerful catalyst for the revolution.The Islamic Revolution and Its Aftermath

The mounting discontent finally erupted in 1978, leading to widespread protests, strikes, and clashes that paralyzed the country. The Shah, weakened by illness and isolated by his own policies, fled Iran in January 1979, paving the way for the return of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and the establishment of a new political order. The Iranian government was changed to an Islamic Republic by Islamic Revolution, a monumental shift that fundamentally altered Iran's trajectory and its relationship with the world. The revolution was not a monolithic movement; it comprised a diverse coalition of secularists, leftists, and Islamists who shared a common goal of overthrowing the Shah. However, once the monarchy was abolished, the Islamist faction, led by Khomeini, quickly consolidated power, marginalizing and suppressing other groups. The new government moved swiftly to implement Islamic law, reverse many of the Shah's secular reforms, and establish a theocratic system. A key event in the immediate aftermath of the revolution was the Iran hostage crisis. Soon afterwards, the Iranian Students Movement (Tahkim Vahdat), with the backing of the new government, took American diplomats hostage at the US embassy in Tehran in November 1979. This act, fueled by anti-American sentiment and a desire to prevent another US-backed coup, severely strained Iran-US relations and contributed to Iran's international isolation. This period marked a dramatic departure from the Shah's pro-Western foreign policy. The revolution also brought about significant changes in governance. The position of the Supreme Leader was established, becoming the ultimate authority in the country. This post was largely ceremonial until July 1989, when a constitutional amendment significantly expanded its powers, solidifying the clerical establishment's control over all aspects of Iranian life. This institutionalization of theocratic rule stood in stark contrast to the Shah's secular monarchy. The legacy of the revolution continues to shape Iran today. While it brought an end to the Shah's authoritarian rule and asserted Iran's independence from foreign influence, it also ushered in a new form of governance that has faced its own challenges, including international sanctions, regional conflicts, and domestic unrest. In phone interviews, people in Iran voiced fear, sorrow and grief after waking up to the news of strikes on the country’s nuclear facilities, illustrating the ongoing geopolitical tensions and the impact of the revolution's legacy on the daily lives of Iranians. The dramatic shift from the Shah's era of Western alignment to the current state of geopolitical tension is a direct consequence of the revolution, making the question of whether the Iranian Shah was good even more complex when viewed through the lens of long-term historical outcomes.Was the Iranian Shah Good? A Concluding Perspective

Assessing whether the Iranian Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was "good" for Iran is a task fraught with historical complexity and emotional resonance. There is no simple yes or no answer, as his reign was a period of profound contradictions, marked by both remarkable progress and severe repression. On one hand, proponents argue that the Shah laid the groundwork for a modern, industrialized Iran. His White Revolution brought significant advancements in education, healthcare, and infrastructure. Women gained unprecedented rights, and the economy experienced substantial growth fueled by oil revenues. He envisioned Iran as a strong, independent nation, a major player on the global stage, and his foreign policy achieved considerable influence for Iran in the region. For many, his era represents a golden age of prosperity and Westernization, a stark contrast to the subsequent decades. On the other hand, critics point to his increasingly authoritarian rule, the brutal suppression of dissent by SAVAK, and the widespread human rights abuses. The rapid pace of his reforms alienated large segments of the population, particularly the religious establishment and traditional communities, who felt their cultural and religious values were under attack. Economic disparities widened, and corruption became endemic, fueling resentment among the masses. His close alignment with the West, especially the United States, led many to view him as a puppet of foreign powers, undermining his legitimacy and fostering a powerful nationalist and anti-imperialist sentiment that ultimately fueled the revolution. Ultimately, the Shah's legacy is a testament to the idea that modernization without popular consent or political freedom can be a dangerous path. He sought to transform Iran from the top down, but in doing so, he failed to address the deep-seated social, economic, and political grievances that simmered beneath the surface. His efforts to make Iran a modern, powerful nation were undeniable, but the methods he employed and the consequences they wrought continue to be debated. The Iranian Shah was good for some, in some ways, and disastrous for others, in different ways. His reign remains a powerful reminder of the intricate interplay between progress, power, and the will of the people. What are your thoughts on the Shah's legacy? Do you believe his reign brought more good than harm, or vice versa? Share your perspective in the comments below. If you found this analysis insightful, consider sharing it with others or exploring our other articles on Iranian history and geopolitics.

Son of Toppled Iranian Shah to Visit Israel

Iranian shah Black and White Stock Photos & Images - Alamy

Iran iranian kings shah persia file hi-res stock photography and images